There comes a point in every home improvement project where I look at the half-assembled collection of raw materials from Home Depot and say “What the hell have I gotten myself into?” I seriously question if I’ve exceeded my skill set. The project always takes longer than my initial estimate.

There comes a point in every home improvement project where I look at the half-assembled collection of raw materials from Home Depot and say “What the hell have I gotten myself into?” I seriously question if I’ve exceeded my skill set. The project always takes longer than my initial estimate.

Novel writing is no different. Stringing together one hundred thousand words with coherence is a daunting task. Then there’s character development, plot twists, pacing, setting, and through it all the nagging fear that on a shelf somewhere what you’re doing has been done before. After the initial, exuberant ten to twenty thousand words, that familiar self-doubt sneaks into the writing room. “What the hell have I gotten myself into?”

A lot of authors I talk to get this feeling, especially those who’ve done a lot of short stories. One beauty of a short story is its brevity. You can plot the three or four scenes the story needs in your head, lay them down on paper, and tweak to perfection. Like building a shed, you know that you’ve raised four solid walls and a roof and all you’re doing is arranging things within.

Not so with the novel. Now you’re building a house. Even with four finished walls, you’re sizing rooms, laying pipe, and running wiring until you type the last chapter. It’s easy to feel lost and overwhelmed.

Your best bet is to just keep plowing ahead. Don’t let the immensity of the project and the endless details, swamp you. Get that first draft finished. If you think of something that doesn’t quite fit with what you’ve written before, just leave a note in the margins to go back and fix it later. Completion gives you a sense of accomplishment and the assurance that you probably do have four walls and a roof. The story now has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Now you can go back and work out the kinks. Some ways to do that:

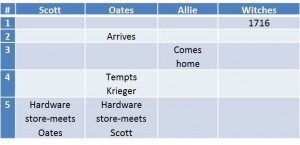

- Look at the overall flow of the story, with two sentences that describe each chapter. See where plot lines intersect. If one story thread goes missing too long, rearrange chapters to keep the thread fresh in the reader’s mind. In a novel like BLACK MAGIC that covers about a week in time, I shifted Thursday events to Monday and they worked better.

- Follow one character at a time through the story. Only review the chapters where that character appears. Are that character’s dialogue and actions consistent? Does that character’s story arc progress plausibly? My novel Q ISLAND has multiple POVs. This method let me refine language for each person, give them consistent usage and common idioms.

- Near the end, scrub that prose. Read the story aloud to yourself, preferably alone so people don’t think you are insane. This method really unearths repetitive words and structures. It also highlights clunky sentences. If a sentence is hard to read aloud, it’s probably hard to read at all. My novella BLOOD RED ROSES frequently uses archaic sentence structures since it is set in 1864. Reading it aloud really helped tune the meter of those sentences within paragraphs to better evoke the time period.

A novel has multiple facets that make it a success. Fine tune your work from one perspective at a time. Like any DIY project, it will probably take more time than you originally estimated.